Tag: n.t. wright

… Have your big scholarly brother step up and speak for you. 🙂

(Original): http://www.ivpress.com/cgi-ivpress/book.pl/review/code=3863 – I find some of these surprising and others not so much.

In speaking of N.T. Wright’s new book, Justification: God’s Plan and Paul’s Vision, responding to and critiquing Piper’s defense of justification, entitled, The Future of Justification, itself critiquing Wright’s understanding of justification, McLaren says, “John Piper, it turns out, has done us all a wonderful favor. In writing the critique that invited this response, he has given Bishop Wright the opportunity to clearly, directly, passionately and concisely summarize many of the key themes of his still-in-process yet already historic scholarly and pastoral project. Wright shows–convincingly–how the comprehensive view of Paul, Romans, justification, Jesus, and the Christian life and mission that he has helped articulate embraces ‘both the truths the Reformers were eager to set forth and also the truths which, in their eagerness, they sidelined.’ Eavesdropping on this conversation will help readers who are new to Wright get into the main themes of his work and the important conversation of which it is a part. And it will give Wright’s critics a clearer sense than ever of what they are rejecting when they cling to their cherished old wineskins of conventional thought.” —Brian McLaren, author A Generous Orthodoxy

In speaking of N.T. Wright’s new book, Justification: God’s Plan and Paul’s Vision, responding to and critiquing Piper’s defense of justification, entitled, The Future of Justification, itself critiquing Wright’s understanding of justification, McLaren says, “John Piper, it turns out, has done us all a wonderful favor. In writing the critique that invited this response, he has given Bishop Wright the opportunity to clearly, directly, passionately and concisely summarize many of the key themes of his still-in-process yet already historic scholarly and pastoral project. Wright shows–convincingly–how the comprehensive view of Paul, Romans, justification, Jesus, and the Christian life and mission that he has helped articulate embraces ‘both the truths the Reformers were eager to set forth and also the truths which, in their eagerness, they sidelined.’ Eavesdropping on this conversation will help readers who are new to Wright get into the main themes of his work and the important conversation of which it is a part. And it will give Wright’s critics a clearer sense than ever of what they are rejecting when they cling to their cherished old wineskins of conventional thought.” —Brian McLaren, author A Generous Orthodoxy

I have now finished reading John Piper’s response to N.T. Wright concerning justification, entitled The Future of Justification. While I could go on about some of the things said in it, there was one particular point that struck me. In critiquing Wright’s understanding of first century, Second Temple Judaism, Piper points out that it very well could be (as Wright asserts) that the first century Jews had doctrines speaking of the grace of God toward them and yet in reality were not resting in that very grace to save them, but relying upon their own supposed self-righteousness to make them right before God in the final judgment.

I have now finished reading John Piper’s response to N.T. Wright concerning justification, entitled The Future of Justification. While I could go on about some of the things said in it, there was one particular point that struck me. In critiquing Wright’s understanding of first century, Second Temple Judaism, Piper points out that it very well could be (as Wright asserts) that the first century Jews had doctrines speaking of the grace of God toward them and yet in reality were not resting in that very grace to save them, but relying upon their own supposed self-righteousness to make them right before God in the final judgment.

This made me start thinking about how many of us in the Evangelical world believe in the grace of God in Christ (as a nice and even excellent theoretical doctrine for many), but in reality do not rest in that grace provided in Christ, just as the Pharisees did not, according to Jesus Himself. This even makes me consider many of the students in our student ministry who seem (at least outwardly) to have no zeal whatsoever for the things of God. I’m not just talking about a zeal to be “good” and “moral,” but a zeal for knowing God more in the Scriptures, seeing His grace in bigger and brighter ways through the work of the cross, and taking that grace to those in our surrounding communities and to our neighbors through missions, ministry work, witnessing, living lives of holiness, … not just to be good, self-righteous, moral people, but to give God glory through works that please and honor Him.

Now I’m not saying this as a blanket statement for all Evangelicals or all students within the ministry I love and volunteer in. But I see and hear a lot of people talk about the grace of God, give the right answers, who talk of the free offer of salvation in Christ, and yet lives go untransformed by grace in reality. It seems many times there is little fruit. Are we really resting in grace, in reality, objectively? Or do we merely believe in it from afar without getting wet, so to speak?

This made me even stop and evaluate my own life, as it should. How can I critique others if I don’t stop and critique myself first? (You know the whole “taking the log out of my own eye to take the spec out of yours” thing?) Do I rest in grace every day? May God have mercy on my soul, because sometimes I don’t in all honesty. When I don’t, the results are evident in my life, for sin and vileness pours forth from my heart in various ways. And my lovely, sweet, selfless wife gets to see the best of that. May God have mercy on me, a grave sinner. This is a call to myself as well to rest in the grace of God alone for all things, salvation and progressive holiness.

Believing versus resting in grace is such a simple distinction with such vast implications for our lives. This is a frightening thought to me: affirming the doctrine of God’s grace without experiencing that grace unto salvation, and of necessity, true inner life-change by the Holy Spirit.

In American Evangelical Christianity, we can wax eloquently about all kinds of orthodox doctrines, have them written out on our websites, or in a pamphlet, and yet when I see the actual effect in people’s lives of these doctrines they propose to believe in, and see startling statistics about how a majority of Evangelicals now believe that Jesus is not the only way to get right with God, I have to wonder about the state of belief in people’s hearts within our own circles. The rampant materialism, the idolatrous pursuit of career as if it could save us from hell, the fake smiles in church toward other people who are absorbed in the same idolatrous materialism we ourselves are mastered by, the singing of songs to God in praise to Him while later cursing in our hearts in all kinds of ways? We need to not only believe in God’s grace, we need to rest in it, experience it in power, by His Spirit alone, in a way that He then effects real change in our hearts.

Can I see into what people are actually thinking and believing? Absolutely not, nor do I presume to. Yet people are making confessions concerning what they say they believe about Christianity and the Gospel that are a far cry from being Biblically accurate. In addition, the outward result in people’s lives is one that is not consistent with that confession (in no way saying people need to be perfect, for that is unbiblical, but that there is no general direction toward holiness). This is concerning to me. It is a frightening prospect: people believing the Gospel in vain. It is something Paul, Peter, John, James and Jesus Himself all warned about repeatedly in the Scriptures. Why is it we hear very little of these warnings in our churches; warnings that are so prevalent in Scripture, almost as much as the grace of God is? May it be because we have succumbed to the worldly culture of “niceness” and “positive thinking” we are absorbed in as a cultural norm nowadays?

As a movement of Christianity, are we merely believing in grace or actually resting in it? Have we come to an end of ourselves and our supposed moral goodness (I mean actually come to an end of ourselves, not just a theoretical doctrine) and have we really rested in Christ alone for salvation? If you rest in grace, you are necessarily believing in it as a stated doctrine. But it is possible to believe in grace as a doctrine without actually experiencing it and resting in it, which is what we need in order to be saved. And may I state this is true even for us in the Reformed community. No one is exempt from this horrible possibility. This is exactly what the Pharisees and many (not all) Jews were doing during Jesus’ time. This makes me think of the frightening passages in Hebrews that speak to this very point:

“Therefore we must pay much closer attention to what we have heard, lest we drift away from it. For since the message declared by angels proved to be reliable, and every transgression or disobedience received a just retribution, how shall we escape if we neglect such a great salvation?” – Hebrews 2:1-3

“For it is impossible, in the case of those who have once been enlightened, who have tasted the heavenly gift, and have shared in the Holy Spirit, and have tasted the goodness of the word of God and the powers of the age to come, and then have fallen away, to restore them again to repentance, since they are crucifying once again the Son of God to their own harm and holding him up to contempt. For land that has drunk the rain that often falls on it, and produces a crop useful to those for whose sake it is cultivated, receives a blessing from God. But if it bears thorns and thistles, it is worthless and near to being cursed, and its end is to be burned.” – Hebrews 6:4-8

“For if we go on sinning deliberately after receiving the knowledge of the truth, there no longer remains a sacrifice for sins, but a fearful expectation of judgment, and a fury of fire that will consume the adversaries. Anyone who has set aside the law of Moses dies without mercy on the evidence of two or three witnesses. How much worse punishment, do you think, will be deserved by the one who has spurned the Son of God, and has profaned the blood of the covenant by which he was sanctified, and has outraged the Spirit of grace? For we know him who said, ‘Vengeance is mine; I will repay.’ And again, ‘The Lord will judge his people.’ It is a fearful thing to fall into the hands of the living God.” – Hebrews 10:26-31

According to these passages and other like them, it is possible to believe in grace (theoretically) and even ascribe it to God as an attribute of His character and nature, and even experience that grace to a degree, and yet not rest in that grace in reality, by His grace alone and thus, as a result of this unbelief, go to hell. THAT is scary, as it is supposed to be. These passages are not in Holy Scripture without good reason, for many many people have gone down this very path. Jesus even said that at the judgment seat in the end of time that, “Not everyone who says to me, ‘Lord, Lord,’ will enter the kingdom of heaven, but the one who does the will of my Father who is in heaven. On that day many will say to me, ‘Lord, Lord, did we not prophesy in your name, and cast out demons in your name, and do many mighty works in your name?’ And then will I declare to them, ‘I never knew you; depart from me, you workers of lawlessness'” (Matthew 7:21-23).

These passages are meant to show us the reality that many people who claim to be not only believers in grace, but “rest-ers” in grace, that though they acknowledge a doctrine (in this instance, the grace of God), their hearts are far from it and are indeed NOT resting in that grace in reality. They are open to condemnation even now as a result (John 3:36). This is the entire history of Israel, back and forth, back and forth, resting in His grace and then falling from it, resulting in God’s punishment. It has also manifested itself in the history of the church time and time again, with various movements resulting from bad (salvation) theology popping up again and again. And yet it seems to have reared it’s ugly head within a majority of Evangelicalism now. We have stated confessions in our churches, on our web sites. But do we really believe the content of those confessions and charters?

Now, “What is the will of the Father who is in heaven,” that Jesus speaks of, you ask? To believe (like really and actually believe and rest) on the name of the only Son of God who united Himself to man, as one of us, lived a life of complete perfection before the Father on our behalf (because we couldn’t), suffered the wrath of God in the place of believing sinners, and rise from the grave triumphant over sin, death, Satan, and hell. If you believe in Him alone, rest in Him alone, trust in Him as the only source of salvation, knowing that in yourself you cannot do a thing to save yourself, but rather trust that Christ interposed His blood on your behalf, you will be saved. “But what if I just can’t believe it? It’s so hard to believe such things!” Cry out to God, just as the father of the possessed boy cried out, “Help my unbelief!” (Mark 9:24). Beg for God’s mercy to open your eyes to the truth of it. It is your only hope.

You must believe this in order to be saved from God’s wrath that we all deserve. But in order to believe even, you must have your heart transplanted by His power alone in order to taste and see that the Lord is good in the first place. Jesus spoke about this very thing to Nicodemus. In John 3:1-15, He said in order to see, let alone enter the Kingdom of Heaven, you must be born again. Nicodemus’ response to Jesus’ statement was one that would naturally result from all of us. “How can a man be born again a second time from his mother’s womb?” But Jesus was not speaking of a second physical birth, but rather of a birth of your spirit, a regenerating of your soul from spiritual death to life. You must be born of God in your inner being, have your spirit made alive by His power alone if you are to see Him, His salvation and thus trust Jesus Christ alone for eternal life.

Here’s my challenge to all of us. Check your soul. Do you believe in the grace of God made possible by the blood of Christ, sealed in His resurrection? Well good … as James says, even the demons believe this … and shudder. The right question is, are you resting in His grace provided for you on the cross? Has the grace of God truly invaded your soul? You will know, for you will see fruit in your life: a desire to pursue Christ, a pain in your soul when you sin, a supernatural joy that cannot be explained any other way than by God’s presence in your inner being, made possible by His effective work in you.

For those of us who are resting in grace, the challenge to us is the same: are we resting in grace not only for salvation, but for true inner life change, and not resting on our supposed moral power and wills to pull ourselves up by our bootstraps to make our lives different? Only God can work in us to change us and make us holy. It is His sovereign power and effective change that we need to be pursuing everyday in Scripture reading/studying, prayer with Christ (as in actual communion with His presence, not just making Him a PEZ dispenser for our various pleasures) and fellowship with other believers who can encourage us and prod us on toward holiness and pleasing the One who saved us and justified us by His grace alone.

In the past, just doing a cursory reading of some of N.T. Wright’s statements on justification, I thought that I could at least grasp a basic concept of his understanding of this centrally important piece of the Gospel message. Then I picked up Piper’s book. Now I’m even more confused than I was before; I now have some clarity on various points, but I see now I haven’t even scratched the surface of where the man is coming from on justification. Wright’s comprehensive picture of God’s working out salvation in history seems to be coming from a totally different avenue, one the church has never been down in 2000 years. It seems Piper is confused at points to, or sees seemingly contradictory understandings within Wright that he is putting out there at various junctures. While reading Piper’s critique and seeing quotes of Wright’s, I think to myself, “This is a Catholic understanding of justification,” and then at other points, I affirm with Wright that part of his articulation is the traditionally historic Protestant view (i.e. the “Wright” one … get it? Wow, okay I’ll stop … you knew it had to come, ya know, a pun … okay I’m digging a hole).

In the past, just doing a cursory reading of some of N.T. Wright’s statements on justification, I thought that I could at least grasp a basic concept of his understanding of this centrally important piece of the Gospel message. Then I picked up Piper’s book. Now I’m even more confused than I was before; I now have some clarity on various points, but I see now I haven’t even scratched the surface of where the man is coming from on justification. Wright’s comprehensive picture of God’s working out salvation in history seems to be coming from a totally different avenue, one the church has never been down in 2000 years. It seems Piper is confused at points to, or sees seemingly contradictory understandings within Wright that he is putting out there at various junctures. While reading Piper’s critique and seeing quotes of Wright’s, I think to myself, “This is a Catholic understanding of justification,” and then at other points, I affirm with Wright that part of his articulation is the traditionally historic Protestant view (i.e. the “Wright” one … get it? Wow, okay I’ll stop … you knew it had to come, ya know, a pun … okay I’m digging a hole).

Things became much clearer tonight though as I continued reading (as much as it can in waters already muddied by a whole new articulation of a super vital doctrine that has never once appeared in all of church history). One of the things that has really come to bear in my understanding of Wright on justification is the way in which he distinguishes present and future justification. I have never even considered these as two separate, yet related doctrines (nor do I at this point still, just so I’m clear … I believe I’m justified now and will be in the future on the same basis, Christ alone). In the present, says Wright, we are justified by faith alone, knowing that all Christ has overcome and achieved is ours, or in other words, the verdict is in: we are His and have been made His by Christ. Okay that’s comforting. Here it comes though … yet future justification, the justification yet to occur at the judgment seat of God, is faith and the entire life lived in love as a confirmation of true, authentic saving faith. Confused?

With Piper, along with Wright, I concur that our lives should be overflowing with good works (imperfectly) from the supposed supernatural change in our hearts we claim to have had happen in us by God’s working alone, and that if that isn’t happening in us now (or we have no desire or struggle even with such things), we should very well question if God has born us anew at all; that is, is our faith the work of God in us alone to save us and keep us, or is it a false faith we worked up out of our sinful flesh that cannot stand the test of time and trials that will inevitably come (and believe me, they will)? If God has created in us a new heart, made us a new creation by the resurrection of Christ, then what necessarily results from that supernatural work in us is sweetness and fruitfulness, not bitterness and rottenness. I affirm this with Piper and Wright.

Wright is correct to point out that so much of Protestantism has erred in not presenting a balanced view of Paul’s understanding of faith and works, that the two go hand in hand. You cannot have one without the other (James 2:14-26). If God brings about faith in your heart, faith that can only come from Him, a faith that is supernaturally struck by the “beauty of His majesty” and the extent to which He went to bring us to Himself, that faith will inevitably produce good fruit because that is what we’ve been redeemed to. Faith and works are indeed interconnected.

But are they interconnected as the basis for our final justification? Or even our present justification? And yet somehow that understanding in itself isn’t connected with my present justification before God’s throne (the very thing that gives me hope when I’ve sinned and fallen short of the glory of God)? Are the two “justification’s” even distinguishable other than by time? I have a hard time accepting that understanding. It’s like a synthesized version of Protestant and Catholic views on justification almost, patching the former into our present justification and the latter into our future justification. Ultimately though, it comes down to our works in his view, from my standpoint.

I affirm with Piper that in Wright’s view of these two “justification’s” (present and future), the basis or root of both is different. In the present, for Wright, justification is rooted in faith alone through Christ alone. Yet in the future, our justification, the final proclamation of our vindication, that we are God’s covenant people, is based on our faith and our whole life lived … or in essence, our works. I agree that faith “works in love” of necessity and the effect of faith is works, but negate the understanding that our justification, either present or future, rests on faith + works in any fashion. This itself is a perversion of the Gospel of Christ and, as Martin Luther said, sola fide (faith alone) was “the very hinge upon which the Reformation turned.”

I have a hard time accepting the idea that my present justification and my future justification are somehow not the same at the root, that is in Christ’s work alone, appropriated through faith alone, that is all granted by God’s grace alone. The thing that gives me hope, everyday, is that both forms of justification, present and future, are exactly the same and are both rooted in the singular saving work of Christ alone, wrought out upon the cross, sealed and confirmed in the resurrection, and applied by His Holy Spirit to His elect covenant people, and in my particular case. It is knowing I’m secured by His grace, that I’m declared righteous, that gives me freedom to work for His glory and honor, because now no longer am I doing it to be justified (or made right with God), but I do it because I want to out of a love that overflows in my heart (all of which is it self a gift a grace).

If in the present I look off into the future justification of my life at the judgment seat of Christ and I see that His judgment of me is based on my faith and the life I’ve lived (or works), and not merely faith alone, will I not attempt to work harder to make sure “I’m in” the covenant community of God? Does my final justification then not hone in and rest upon what I’ve done in my life, which is defiled and wretched? What hope is that?

You see then, in all reality, if I believed this, ultimately the final verdict of whether or not I go to heaven or hell depends on my obedience, my works, which once again hits at the very distinguishing mark between Protestants and Catholics for 500 years (which Wright, in my opinion is folding on doctrinally): for Catholics, their justification, or right standing before God, comes by faith and works, produced by the infusion of the Holy Spirit into their hearts; for Protestants, our justification is through faith alone, that we are accounted righteous by Christ’s working on our behalf … but we saved through a faith that works in love of necessity … because the faith that God grants His people is of Himself and full of power, effectively changing the course of our entire lives (though we still yet remain imperfect). Ephesians 2:8-10 articulates this Protestant doctrine the best: “For by grace you have been saved through faith. And this is not your own doing; it is the gift of God, not a result of works, so that no one may boast. For we are his workmanship, created in Christ Jesus for good works, which God prepared beforehand, that we should walk in them.” God saves His people by grace, granting faith, which justifies them, and then He moves in them to work for His glory.

I find all of this highly confusing, especially to those who have only a fundamental understanding of what justification is, let alone Wright coming along and making distinguishing marks between two different kinds, a present and a future justification. Wright says the Reformers were confused on the issue and that the conversation between Protestants and Catholics got off on the wrong foot during the Reformation. But I can only say Wright seems to have confused himself 1) about what the Reformers were saying concerning faith and works, and 2) he may be reading too much Second Temple Judaism back into the texts of Romans and Galatians in particular.

But, I am no scholar, nor do I presume to be, nor have I read any Second Temple Judaism from which to make any kind of a standing assertion such as that. I have only grasped a few of the concepts Wright is articulating, or at the very least attempting to, so I could very well be wrong and misunderstanding what he is saying. As you study, one of the things you realize is just how little you know of anything really. If Piper is confused at points, surely I’m going to be. Somehow I feel that Piper’s confusion comes from (possible) contradictory statements and a (possibly) confused N.T. Wright who is uttering them. But maybe I have a bias.

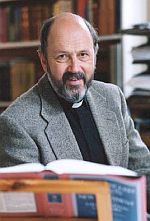

N.T. Wright, the Bishop of Durham in the Church of England, is by far one of the most scholarly, well-read, intelligent people of the modern church. It is no wonder people from all different points of view are flocking to him for answers to all kinds of things pertaining to theology and history. His impact can be felt both in the secular academic world as well as the theological world within Christianity.

N.T. Wright, the Bishop of Durham in the Church of England, is by far one of the most scholarly, well-read, intelligent people of the modern church. It is no wonder people from all different points of view are flocking to him for answers to all kinds of things pertaining to theology and history. His impact can be felt both in the secular academic world as well as the theological world within Christianity.

So what are we to make of him? Well, there are many things we can outright affirm with N.T. Wright, one example being the resurrection of Christ. He is a relentless defender of the historical resurrection of Jesus, having written extensively to show this to be not just a myth or tradition within the church, but a reality. We should all be very grateful for someone of his education and knowledge to be on our side in this matter against the heresies raised against this pillar doctrine of the church.

In addition to defending the resurrection, he is an excellent historian, having brought much knowledge in the way of first century Judaism. Understanding this historical context is vital to understanding the thought, issues and problems dealt with in the New Testament. He has done a massive amount of writing and contributed greatly to our appreciation for and understanding of first century Judaism. As believers, we would all do well to read his works on both the resurrection and first century history. We are indebted to his work in regard to both of these areas.

But what problems are there? Unfortunately, there are a few things we must be very careful on, the main thing I’ll speak about being Justification. I will stick with this because it is the biggest controversial point of his theology. In theological circles this has been labeled the New Perspective on Paul, though by no mean is he the first to advocate this position. And by no means is he advocating it in the same way the forerunners of this position did.

Because of Wright’s knowledge in the area of first century Judaism, his reading of the Reformational (Protestant, evangelical) understanding of Justification within Romans and Galatians in particular (Justification by grace alone through faith alone in Christ alone), seems to have been affected. He reasons that terms in these books of Scripture such as “works of the law,” “justification,” amongst other terms used by Paul in relation to salvation, must be understood through the lens of first century Judaism, not the Reformers.

In addition, Wright says that continuing to read these terms in light of the Reformation is erroneous. He argues that we must go back to the surrounding cultural Jewish texts, looking past the Reformational writings, and even Augustine’s work in the third and fourth centuries, (something he has definitely done, I’ll give him that) and understand that these terms do not carry the Reformational meaning we all have become accustom to.

My question (as a side point): so are we now sliding back toward Rome after having gone through such a tremendous theological shift from her in the Reformation? Francis Beckwith’s departure from evangelicalism back into full communion with the RCC sure does seem to indicate so. He’s not the only one too. Many theologians within evangelicalism are now blurring the lines of distinction between the RCC and evangelical churches on the point of Justification.

Anyway, Wright is essentially saying that the Reformers are reading an understanding into these terms (and thus unto Justification) that is not there. This has all kinds of implications, and more broadly, this understanding creates a whole new systematic theology, because all points of theology are affected by the other points inevitably.

If that is true concerning those terms, what are we to make of the Protestant understanding of Justification? Well, Wright seems to reason that Justification, as Paul used it, refers primarily to our inclusion into the community of believers. According to him, the Reformers were bringing unnecessary presuppositions to the text, and having come out of such political and theological abuses by the Roman Catholic Church, the Reformers were radically departing from the Roman Catholic understanding. Essentially, he is saying the Reformers were swinging a bit too far and throwing the baby out with the bath water.

Hmm. There is more to the argument, but I’m not smart enough to grasp the entirety of it to be honest. This is what I have “gotten” so far though. That may be a reductionistic explanation (I’m willing to learn on this), but that’s what I have understood from it thus far. To be fair, I do not believe he rejects the Reformers theological understanding in its totality, but it seems to me at least he is rejecting the Reformers understanding of Justification.

As it relates to Justification, the main problem that arises out of all of this is the nature of imputation, that is Christ’s perfect record and righteousness being credited to our account through His work in His life, death and resurrection, at least as understood in the recovery of the Gospel during the Reformation. If Justification is simply about being in or out of the community of believers, then my question is, why did Paul seem to make the argument a legal one in both Romans and Galatians? And why did he seem to always relate his explanation to salvation and eternal life? Was it or was it not about eternal salvation, or just inclusion within (or exclusion from) the community of believers?

Also, Wright makes the argument that the term “works of the law” in first century Judaism meant a “badge of honor” (or pride) within the community. So he goes on to say that in Galatians, for example, Paul is not making an argument that the Galatians were trusting in their “works of the law” to save them eternally, but that they were merely being prideful and excluding those who did not adhere to the same “works of the law” they were adhering to. Also, the one big thing I have a problem with in all of this is Paul’s statement in Galatians 4:11 which says, “I am afraid I may have labored over you in vain.” Is that a statement just about the Galatians including or excluding people merely? Or was it that they were eclipsing the Gospel by their supposed self-righteousness? I tend to think the latter.

This almost sounds like the same type of argument Arminians make in Romans 9 to say that what is being spoken of there is not the unconditional election of individuals to eternal salvation, but rather a temporal,corporate election of groups to historical roles. They both make the focus of the text temporal instead of eternal. Wright is way smarter than I ever will be though, and so I’m sure he could blow me away with some forceful argument as to how that is not what he is doing. But I just think his understanding may seem plausible, but in reality strays from what was recovered in the Reformation, that Christ’s work alone is what saves us. The Gospel itself is at stake in this debate.

Do you see how tricky all of this gets now? Quite a mess if you ask me. Wright’s arguments totally redefine the whole nature of the Gospel itself against the Roman Catholic Church’s understanding of how we are saved and makes it one with a temporal focus instead of an eternal one. More than that, it opens the way, once again, for making works apart of our final justification, and thus turning Christianity into every other religion that says, “Do this and you shall live,” as opposed to the grace of the Gospel which says, “You can’t do this, Christ substituted places with you, and now you shall live.” Wright inherently seems to share their understanding that within our justification is included our sanctification, that is our works, because according to both of them (Wright and the RCC), Justification is the whole of the Christian life, instead of a once for all time declaration at the cross. There are a ton of other points of theology that are affected by this understanding. This is the most controversial though. This only scratches the surface.

So in summation, Wright’s works on first century Judaism and the resurrection of Christ should definitely be read and thought over. We should even use it in defense of the supremacy of Christ in our apologetic and evangelism work. Much progress has been made in defending the resurrection of Christ. But Wright’s theological and Scriptural understanding of Justification in particular should be read with great caution and warning. John Piper has written a book addressing the whole New Perspective, in defense of the historical, Reformational understanding. To me, Wright’s understanding has essentially paved the way for works to “re-enter” the understanding of evangelicals as it pertains to our Justification before God, one of the very reasons the Reformation was started to begin with.

Some more information on the New Perspective and N.T. Wright:

John Piper’s book against the New Perspective, responding to N.T. Wright in particular: http://www.monergismbooks.com/The-Futur … 17450.html

New Perspective section on Monergism.com: http://www.monergism.com/directory/link … rspective/